Published by: Ezra Dyer | March 17, 2024

The debut of a new engine used to be a semi-regular occasion. As cars evolved, so did their powerplants, and manufacturers regularly made seven-figure investments to develop new engines. With the EV transition in full swing, that's no longer the case. Major companies like Volkswagen have been announcing that there will be no new internal-combustion engines in the pipeline and multiple manufacturers have pledged to go all-EV by 2040.

But the marine industry is a different story, and in recent years some of the coolest new engines—Mercury's V-12, Honda's V-8—were designed for boats. Which is also the case for Yamaha's new 1.9-liter four-cylinder, which makes 200 hp at 7600 rpm and can be found powering high-output WaveRunners and jet-drive boats. It's not designed for cars, but the Lemons racers among us can dare to dream.

The 1.9-liter four replaces Yamaha's 180-hp 1.8-liter mill and blurs the performance line between the company's naturally aspirated and supercharged engines. Yamaha's supercharged 1.8-liter makes 255 horsepower, but in a WaveRunner there's not a huge practical difference between the boosted 1.8 in a SVHO model and the naturally aspirated 1.9 that powers HOs. Personal-watercraft manufacturers adhere to an agreement that's something like the old German pact to limit top speeds to 155 mph, except on the water the target is 65 mph. That spec includes a 2-mph fudge factor, which naturally means that PWCs of sufficient horsepower top out at an electronically limited 67 mph. Since a 200-hp WaveRunner can hit that limit, the only difference is how quick you get there.

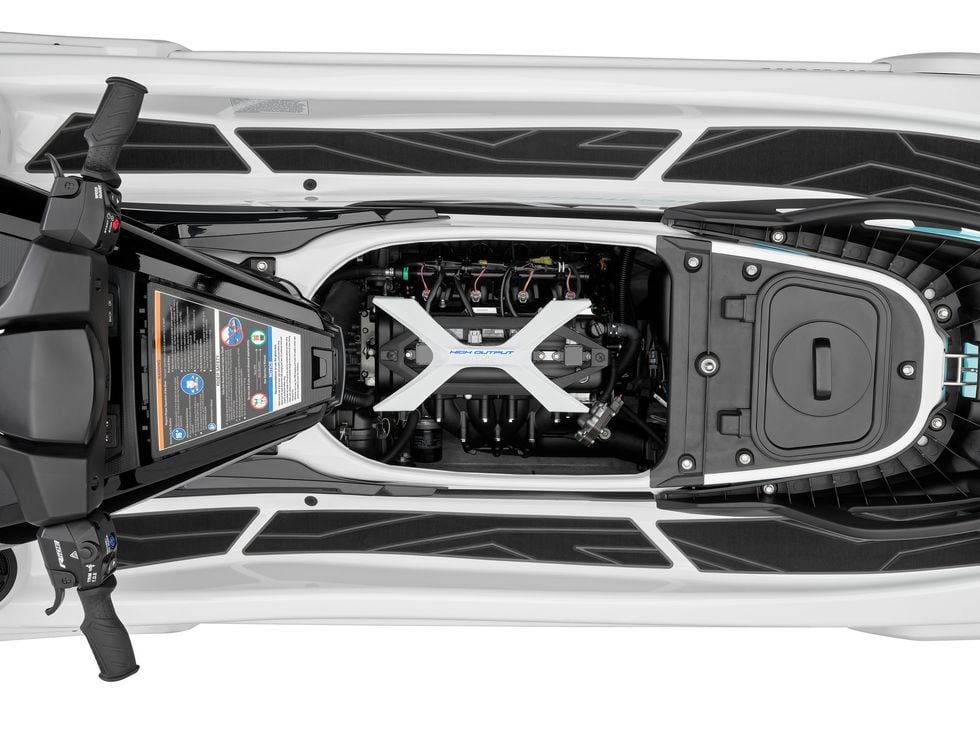

The 1.9-liter, as a new design, enjoys a bundle of changes aimed at durability and refinement. One example: There's an extra bolt connecting the cam chain housing to the block—a little tweak that makes a big difference. "The cam chain room is a thin aluminum casting," says Mark Sagers, senior watercraft factory service technical specialist (in other words, the guy who knows all the engines inside out). "That great big straight piece of aluminum is like a sound board, amplifying the noise of the cam chain. But if you run a fastener from that to the main casting, it knocks that noise way down. That's important when you're sitting right on top of the engine and it's bolted to a guitar body, basically."

Performance-enhancing upgrades include a new exhaust manifold with dedicated pipes for cylinders one and four, a bore increase from 86 mm to 88 mm, and a channel to route cooling water between the exhaust valves to cool the valve seats. The 1.9 even uses about a half-quart less oil than the 1.8, because Yamaha determined that it could cut windage losses (read: increase horsepower) without sacrificing durability. And durability versus performance is always a tradeoff, whether on land or not. "In a 250-cc motocross bike, the maintenance schedule calls for a new piston every nine hours and it's putting out specific power like a NASCAR engine, or almost Indy," says Sagers. "Boats are more on the lower end of high performance, so we can make them last thousands of hours."

A car engine might well make its horsepower peak beyond 7000 rpm, but it isn't expected to spend much time there. An engine destined for a WaveRunner is a different story. "A lot of the durability testing is done fully loaded at wide open throttle," Sagers says. "These will run a very long time at WOT. Waverunners are often idling or WOT, and there's no middle ground. But I've seen Waverunner engines with more than 1500 hours and no major mechanical work. It's staggering that these mechanical things can live through this."

Still, 200 hp isn't enough for everyone. Logically, it would seem inevitable that this engine will get a supercharger and the 1.8-liter will be retired. Boost prognosticators might find a clue at the 1.9-liter's Coast Guard–mandated intake flame arrester—the intake manifold is cast around it so it can't be sucked into the engine. Which is the kind of thing that would probably only happen if said intake was huffing some major boost. Perhaps soon, it will be.

In the meantime, you can break the 200-hp barrier without forced induction. And for twin-engine boats, that means Yamaha is packing 400 horsepower into some of its 22-footers, which we imagine would mean 50-plus-mph top speeds given that the 210 FSH hit 48.0 mph with the 1.8s and their 360 total horsepower.

Yamaha has built some nice automotive engines—most famously, the Ford Taurus SHO's—but those of us dreaming of 200-hp Yamaha-powered Miatas will probably have to wait a while for these latest ones to hit the salvage yards. (You can spend that interim figuring out how to adapt a closed-loop cooling system, since the jet drive on these engines doubles as a water pump.)

Calling a powerplant a "boat motor" is traditionally a pejorative, meaning a low-revving hunk of iron, an outdated castoff better suited as a mooring. But motors are electric, and that's where things are heading on the highways. So if you appreciate the mechanical complexity and cleverness of engines, boats are the new—and maybe last—frontier.